The quote well articulates the purpose and motivation behind architectural criticism. Less the personal opinion of the critic, more the possible illumination and betterment of the society, or within the context of the school of architecture, design education of the student. The title of this essay rephrases Kicked a Building Lately? the 1973 book written by the late architectural critic Ada-Louise Huxtable. It aims to offer observations found in today’s architectural criticism in the school of architecture, particularly through the lens of Hong Kong where I currently teach. Kicked a Project Lately? is meant to illustrate the idiosyncrasy and nuanced exchanges that occur between the studio instructor, the guest critic, the student, and the audience during the design review.

Critic Sees

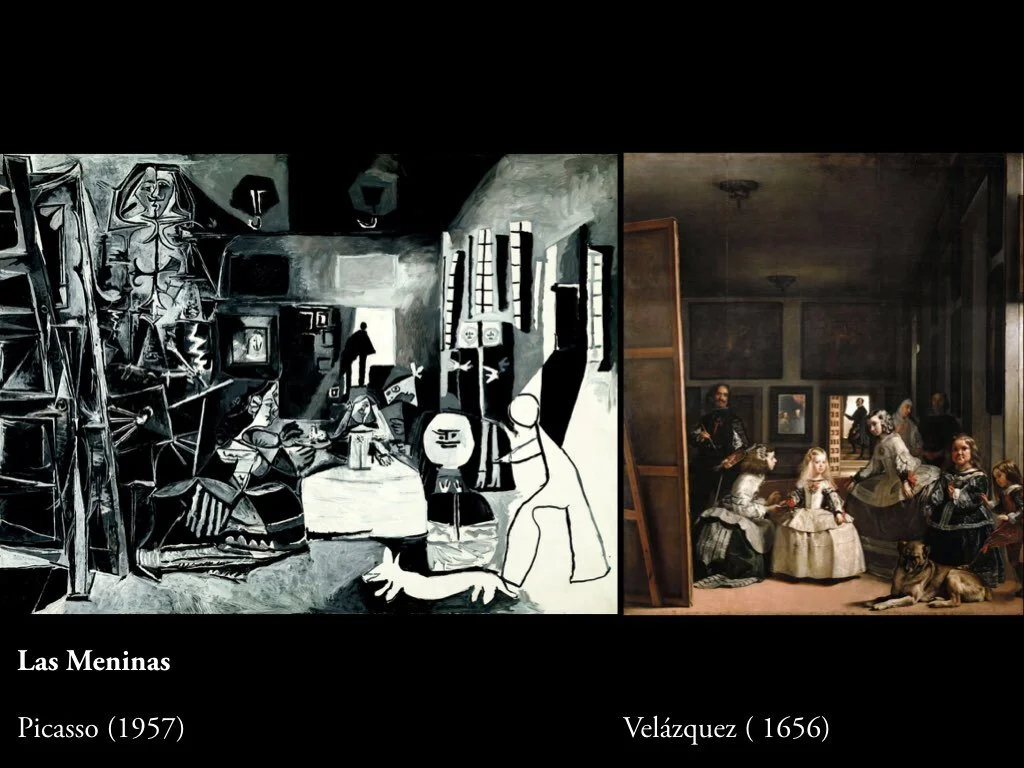

In 1960s, the American artist Jasper Johns made a series of drawings and sculptural reliefs making parody between the art critics and the apparatus they helped to create. In The Critic Smiles, he made visible the much-desired blessings from the critic by mounting four human teeth on a toothbrush. This détournement assembly of the oral parts and the hygienic product mocks the interdependent and inimical dynamic between the artist and the critic. As if to suggest the critic is the “domesticated barbarian who rips apart the artwork with his clever words”. In The Critic Sees, Johns materialises “the pathetic situation of the critic who is unable to apprehend anything beyond his own words, opinions, and preconceived notions about art” as asserted by the art historian Roni Feinstein.

Unlike what could be interpreted as an adversarial relationship between the critic and the artist. In the school of architecture, criticism plays an indispensable part in the education of the architect-to-be. Criticism is the battleground where the conceptual motivation and the representing object it aims to signify are put forth by the student as an intellectual construct. The critic is the experienced professional who oversees the battle.

What do you think of this?

For those of us who are studio instructors, we are being addressed as a critic when we hear this question. Each week, once or twice with around twenty students, we engage each student in a twenty-minutes dialogue, Q & A, critique session on the development of the project. Simply responding by “I like it” is not only unacceptable but it is frowned upon. Instead, we are requested, by the power associated with us as the 'the critic' to probe into the design, the drawings, the models, and the incomprehensible diagrams, sketches, notes and sometimes, “nothingness" to reveal the incongruence between conception, perception and effect. Even delving deep into the inner psyche and the emotional state of the students by asking "How is your mood?" or "How do you feel?”, more akin to consultation at the shrink's office than a traditional classroom interaction.

Ritual

For anyone who has gone through formal education in architecture, getting critiqued is a normal affair. A seasoned student standing on the receiving end of the critique by a panel of expert jury can sometimes be as uneventful as pairing wasabi with nigiri. Yet, just like the raw and shattering power of tasting wasabi as an amateur, getting a critique for the first time could be a tearful and mouth-shattering experience.

The incremental feedback system of the critique has been a part of the design education since the mid-eighteenth century beginning from the École des Beaux-Arts. The format of jury system which started in Europe and proliferated during the Twentieth century has made a globalised architectural education possible. Walking into any school of architecture around the world, one immediately understands the modus operandi.

The critique or the “crit” is intended to be an interactive way of evaluating and enhancing the quality of the architectural project. It is the place where design ideas are: “introduced, explained, discussed, evaluated, defended, appended, discarded, rejuvenated, and consolidated.” It offers a platform for the student to clarify her line of thinking and to develop a cohesive way of addressing the project through the assistance of the crit. The critic gives feedback to a broad range of subjects, from the humanities, graphics to the technical. The conduciveness of the crit depends on several factors such as, composition of the jury (race, gender and age), quality and commitment of the student and critic, size of the jury, media for which the project is presented, space where the presentation takes place, etc.

David and Goliath?

Leading and participating in a critique can at times feel like a boxing match. The two opponents, each represented by the student and the critic engaged in a match while a body of spectators looks-on with great cheer and awe. Usually, the inherent imbalance of the power structure, differences in experience and knowledge between the critic and the student rid of any possibility for the student to win the match. Nevertheless, the legend of overcoming the powerful Goliath offers one of the key attractions for the spectators.

The crit can take many forms. From a one-on-one desk crit between the studio instructor and the student that is highly intimate– the Sparring Session. To the theatrics of a thesis review involving a panel of external juries in– the Title Fight. Or, in between these poles other arrangements such as pinups of work-in-progress sketches, quick prints, and paperless presentations– the Exhibition fight, each designed for a particular purpose. Like the rules for professional boxing, the arrangement for the crit is well-understood by those in attendance. Not much is different here in Hong Kong, with even the occasional ringing of the bell to stop the crit.

Authority

The critic assumes the role of the judge which exudes an aura of authority. An authority whose command and mastery of the subject matter supremes over the students. Commentary and advice all come with an absolute and definitive undertone, plus an occasional hint of mysticism. This initial perception of the critic’s capability is shaped in part by architecture being a professional programme. As if one could draw a parallel between an analysis of a misappropriated use of symmetry in the design of a cenotaph by an architectural critic, to that of a patient being diagnosed with an early form of coronary artery disease by a doctor.

Sometimes the authority is an elderly gentleman with a suit and tie who speaks with a deeply accented voice. But more often than not, it is a young man in his early 30's that we see in the School who wears a Paul Smith shirt holding a cup of black coffee from a local boutique café in his hand. The young critic arrives at the school ready to mingle. With his eyes set on the look-out for the next important persons in the room, where he is ready to recite his long-form curriculum vitae.

Despite his youthful appearance, the critic is someone of a particular expertise and knowhow— so thinks the motivated year-one student. For why else would the critic be there in the first place? The student soon learns by year-three that the critic is not always the authority he is assumed or projected-to-be but in fact, someone who wishes to be away from the mundane of and relief from the every day architectural practice.

To return to the crit room is for him, a rekindling with the naiveté he once felt. That fuzzy feeling of optimism which propelled him to study architecture in the first place. So, in order to regain that nostalgic urge of making the world a better place, the critic accepts the invitation to attend the mid-review. Even at his own expense of salary deduction by taking 5-hours away from the office, before having to return to the routine afterwards.

Contest

Sometimes the critic can sense that their authority is being challenged in public when the student disagrees or offer a critical defence to their comments. When that happens, the critics are compelled to hit back so to reclaim their authority and save face in front of his colleagues, students, and audience. This defensive act is often revealed through the changing tone of the critic.

Every so often the critics are competitive with each other, where one critic tries to out-theorise, out-critical and outwit the other. Each attempt to identify the most nuanced graphic or verbal “error” by the student so to deliver a spectacular and devastating blow. When such instance occurs, the critic is essentially dismissing the main purpose of the crit.

It is also interesting to witness the crit being transformed into a propagandist platform to duel-out old and unfinished business. Many critics within the small circle of architecture are aware of each other’s viewpoints and positions. Therefore the critics can arrive at the crit ready to either prophesies the future, or reclaim the wonders of the past, or anything in between. Advocating ideologies to advance their own cause. Minions of Parametricism, New Urbanism, Projectivist, OMA-New Ruralism, Sustainable Opportunism and do-gooders of the Bottom-Up-Community-Advocacy are just some of the examples. It often goes go on as if the student and the project pinned-up are absent from the critic’s field of vision. In these situations, the critic’s aim is no longer centred on the student but eyeing instead, for the attention of the audiences in the room. This kind of debates, although highly relevant, diverts the critique from its primary purposes.

Convoluted

Being an effective critic is by no means an easy task. In a review, the critic is expected to find something to say even when he is bored, dazed, spaced-out and speechless. In those instances, the critic might be tongue-tied, inarticulate and all over the place with his comments like a headless fruit-fly flapping and buzzing his wings without any direction. As such performance plays out, the critique becomes confusing, distracting and brings no constructive message to the presenting student.

To be clear-headed about what to say, and to focus on the weak elements with rooms for improvement. The fully concentrated critic needs to communicate clearly through succinct comments, typically under just a few minutes. The criticism not only has to be reasoned, it also aspires to be enlightening, provocative and humorous so to sustain the short attention span of the Twitter or Weibo-age Millennials.

Short of doing so results in further detachments by the students since they do not always see the relevance of the comments made, references cited and the allegory being thrown at the student by the critic. As such, the student is often passive and standing idle, waiting for the end to come.

Double-dip

Hong Kong adopted a 3+1+2 legacy pedagogical system from the British RIBA. It is a three-year bachelor programme with one-year internship and a two-year master's education. This structure offers a flexible arrangement for those students unsure of their choice of major.

As opposed to being labelled a drop-out midway from a five-year programme, it gives some the possibility to pursue an alternate choice of study upon receiving the Bachelor degree. For many who are determined and wishes to pursue a professional degree, the students will return to their alma mater to get the Master’s degree thus creating a double dipping phenomenon.

Blasé attitude

What often happens after spending roughly a year as an intern, or year-out, in an architectural practice where the student has the chance to get baptised by the ‘real’ world, is that they return to the graduate programme with a higher degree of confidence. Not with the intellectual understanding of what architecture is, but how architecture is practised, at least in the everyday setting of Hong Kong.

The double dip phenomenon allows the studio instructors to witnessed the difference, before and after the internship. Although the unquestioning, agreeable and unantagonistic behaviour of the standard-bearer of a Hong Kong student still persists. The once virgin-eyed year-one student is now superseded by a skeptical one. Conveying through her dismissive gaze to the critic what it is like to be out there. “We have been to the outside, I have seen the real world, you know?” as if the instructor was an orphan born in the ivory tower.

What we witness is the becoming of the blasé attitude of the double-dipping student. She is no longer the student itching for the next opportunity for a crit with the instructor, instead, looks for the right moment to split from the next conversation. The naiveté of believing the authority is the person sitting across from her is now history.

Virtuoso: The Deconstructivist

Sooner or later the critic is able to redeem himself. Particularly when the aura-possessed virtuoso ‘The Critic’ shows up to the reviews. Or, occasionally referred to as the "butcher is in da slaughterhouse"! It is the moment when the critic regains his reputation from the blasé student.

I once heard Bernard Tschumi made the assertion that the best critics are those who can break down a project before building it back up. Every now and then such virtuoso does appear among us, the average critic. With The Critic, a.k.a. the butcher sitting among us, we began listening carefully to the presenting student on her motivation to reinvent the museum typology. After a round of evaluation goes by, the butcher begins to speak.

The bona fide critic began deconstructing the project by transgressing its internal logic. Through deciphering the elemental components, the connoisseur is able to arrive at the heart of the rationale for the concept. Able to drill down to the bottom of the truth and nothing but the truth, citing passages from Sennett and Foucault along the way.

As if he is unaware of the strength of his own analysis, The Critic goes on to crack open the specific deficiencies of the drawing by citing its lack of fluidity in its lines. The usual method of model-making also falls victim to the round of critique. Finally attacking the giant divergence between the motivation and the production of work plastered around the walls and floor of the crit room.

Kicking the project down on a path as if it is unworthy of any comments for the next five minutes without a pause. The negative sentiment would not be the end of the critique. Instead, just when the devastated student was about to pin down and leave, The Critic takes a turn making it right.

Virtuoso: The Builder

The Critic spends yet another five minutes building the project back up with all the promises and glories that one could imagine borne out of a piece of white paper, or a Ju Ming sculpture popping out of a stone quarry. Describing the potentiality of the fluid-deficient lines as the student’s strongest asset yet. Arguing that it represents a form of robust resistance to the contemporary kitsch museum discourse. The connoisseur critic builds upon the students verbal presentation, graphic and three-dimensional representation into a cohesively considered proposition.

Eventually, the student's leaves the session perplexed, yet exhilarated. Should she feel good about her project, or should she restart from the blank slate? This question becomes the intellectual struggle for the next three days. The student is stimulated into thinking critically for herself.

The skilful critic described by Tschumi does not come often. But from time to time, the gentleman does appear. At its best, the critic is both feared and loved by the students. A sentiment not exclusive in the academy but in practice as well. “I wanted her attention, but I was scared of it…. She was tough, but her words were beautiful” recalled Frank Gehry when attending Ada-Louise Huxtable's memorial on June 4, 2013.

Practicing the Kick

Great criticism rarely affirms the status quo. When the critic engages in a project, he listens intently and looks for inherent inconsistencies. He points to gaps where others saw none, gaps between “drawing and design, plan and occupancy, projection and imagination, and he finds order in places where others thought it did not exist.”

"Feared by some architects, loathed by some developers and not universally admired by scholars.” The qualities that epitomise who Ms. Huxtable was, reflects the best in a critic. As a student in the art of architectural criticism for the past eight years, I remain humbled and thrilled by the opportunity to offer judgements on student’s imagination to make a better world.

Whether it is for a simple proposal of designing a Room for Reading, an introductory project catered for high school students interested in architecture. Or, a nuanced, provocative and complex proposition of a thesis project for candidates of Master of Architecture. Making a constructive and enlightening criticism remains a challenging task. As such, for my part, I will continue to practice my kick for the betterment of the students.